- New Arrivals

Fiction

- Historical FictionCrime & ThrillersMysteryScience-FictionFantasyPoetryRomanceChildren’s BooksYoung Adult

- Biographies & MemoirsHistoryCurrent AffairsTech & ScienceBusinessSelf-DevelopmentTravelThe ArtsFood & WineReligion & SpiritualitySportsHumor

Children’s Books

Lists

Blog

Gift Cards

My Lists

Games

The co-op bookstore for avid readers

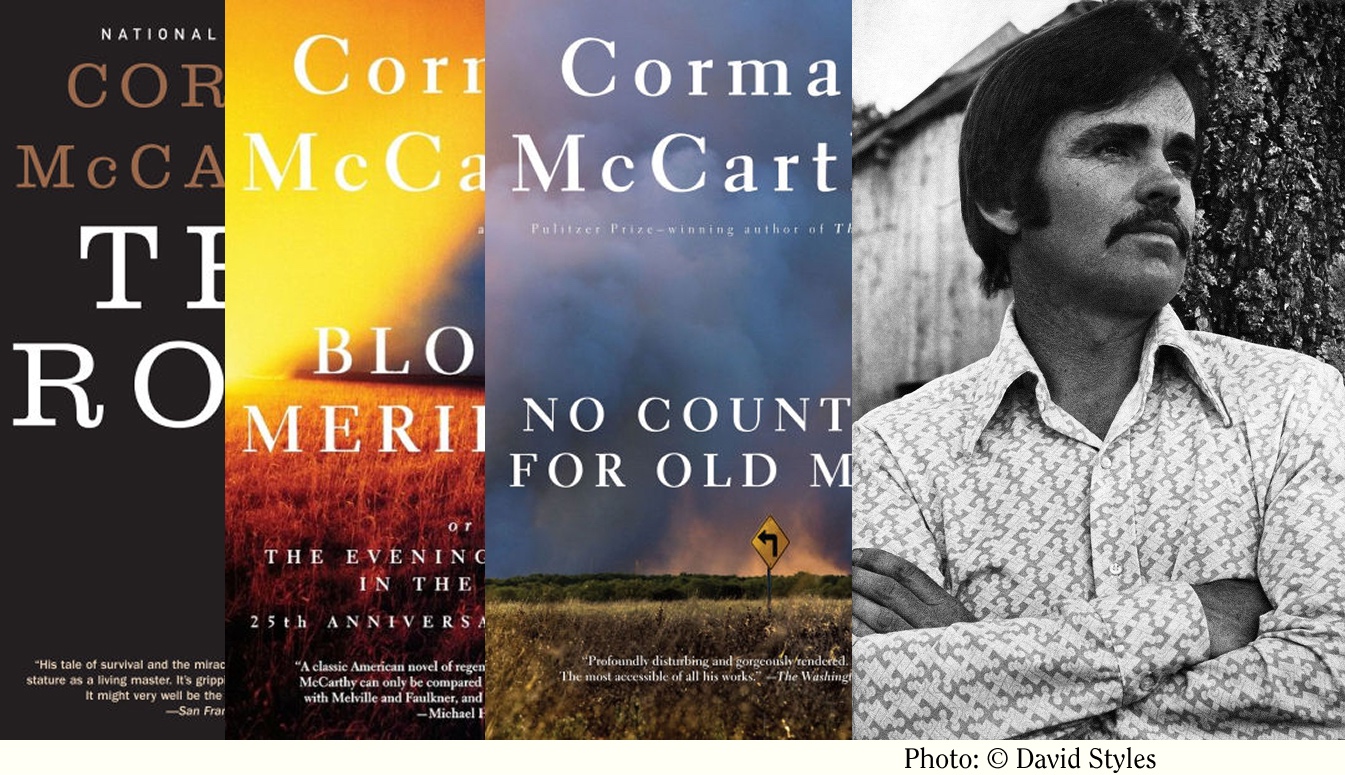

The Complete Works of Cormac McCarthy in Order

Few writers have charted the bleak edges of the American soul quite like Cormac McCarthy. Over a career spanning six decades, his fiction moved from the decaying backwoods of Appalachia to the sun-bleached desolation of the American Southwest—always driven by haunting prose and a mythic sensibility.

McCarthy died in 2023, leaving behind one of the most powerful and enigmatic bodies of work in American literature. Across twelve novels, in addition to plays and screenplays, he mapped both the physical and metaphysical contours of the nation, blending biblical cadence, existential dread, and stark violence into something entirely his own. Word has it that two major biographies of McCarthy are coming out later this year, and we can’t wait for the inside scoop about his life and work, especially after the bombshell reporting in this controversial Vanity Fair piece last year about his secret muse.

1. The Orchard Keeper (1965)

McCarthy’s debut novel, The Orchard Keeper, unfolds in the backwoods of rural Tennessee, weaving a dense, elliptical story of a bootlegger, a young boy, and an old man unknowingly tied together by an unspoken killing. Drawing comparisons to Faulkner for its stream-of-consciousness narration and dense regional dialects, the novel marked McCarthy as a fiercely original talent. Though its plot resists easy summary, the book’s mood of decay, isolation, and violent memory would echo throughout his career. It won the William Faulkner Foundation Award for a notable first novel, establishing him as a writer of serious talent.

2. Outer Dark (1968)

In Outer Dark, McCarthy deepens his Southern Gothic vision, following a nameless brother and sister through an unnamed Appalachian landscape after their incestuous child is abandoned. The woman searches for her child; the man flees his guilt—and a trio of spectral figures trail behind them, leaving carnage in their wake. Bleak, dreamlike, and shot through with a sense of cosmic indifference, it’s a grim parable, marking McCarthy’s shift from regional realism toward something closer to allegorical horror.

3. Child of God (1973)

Perhaps McCarthy’s most shocking work, Child of God tells the story of Lester Ballard, a dispossessed and depraved man exiled from society who descends into necrophilia and murder in the hills of Tennessee. Based loosely on true events, the novel is as disturbing as it is artful, written in McCarthy’s cool, detached style that refuses to moralize. It’s a meditation on what lies beyond the margins of civilization, where a man reduced to his most animal instincts still clings to some distorted idea of humanity. Controversial and grotesque, Child of God is nevertheless a brilliant early example of McCarthy’s ability to render horror with lyricism.

4. Suttree (1979)

Set in 1950s Knoxville, Suttree centers on Cornelius Suttree, a man who abandons his upper-middle-class upbringing to live among drunks, misfits, and fishermen on the banks of the Tennessee River. It’s McCarthy’s most autobiographical novel, and his most expansive in tone—by turns tragic, comic, and grotesque. Unlike the terse violence of his earlier books, Suttree revels in richness: of language, character, and philosophical rumination. It took McCarthy over two decades to write and remains a fan favorite, considered by many to be his most personal and emotionally resonant work.

5. Blood Meridian (1985)

A towering achievement in American literature, Blood Meridian reimagines the Western as a hallucinatory epic of violence. Following “the Kid,” a runaway who joins a gang of scalp hunters led by the terrifying Judge Holden, the novel traverses the Texas-Mexico borderlands in the mid-1800s, chronicling a near-mythic spree of bloodshed. Dense with biblical allusion and historical detail, the book is an unflinching examination of violence as a force beyond morality. Despite being largely overlooked upon release, it has since been hailed as McCarthy’s masterpiece—described by critics like Harold Bloom as one of the greatest American novels ever written.

6. All the Pretty Horses (1992) | The Border Trilogy

With All the Pretty Horses, McCarthy found both critical acclaim and commercial success. The novel follows 16-year-old John Grady Cole as he leaves his fading Texas ranch for the romantic promise of Mexico, where he encounters love, betrayal, and the brutal realities of life beyond borders. The book is steeped in the melancholic beauty of the dying West and written in a more accessible style than his earlier works. It won both the National Book Award and the National Book Critics Circle Award, introducing McCarthy to a broader readership and launching the Border Trilogy.

7. The Crossing (1994) | The Border Trilogy

The second volume in the Border Trilogy, The Crossing centers on Billy Parham, a teenage boy who traps a pregnant wolf and decides to return her to the Mexican mountains—an act that becomes a spiritual quest. The novel spans years and landscapes, blending fable-like encounters with profound meditations on the unknowable forces of existence. More solemn and philosophical than All the Pretty Horses, it deepens the trilogy’s exploration of moral complexity and the irretrievable loss of innocence.

8. Cities of the Plain (1998) | The Border Trilogy

In the concluding volume of the Border Trilogy, John Grady Cole and Billy Parham—now grown men and ranch hands in 1950s New Mexico—become close friends. Tragedy ensues when John Grady falls in love with a young Mexican prostitute, leading to a doomed love affair and a violent climax. Cities of the Plain is a quiet elegy for the cowboy ideal, haunted by the ghosts of previous novels. The book is a fitting end to McCarthy’s vision of the borderlands.

9. No Country for Old Men (2005)

Originally conceived as a screenplay, No Country for Old Men is a taut, propulsive thriller that explores the moral and generational decline of modern America. Set in the Texas desert during the 1980s, it follows Llewelyn Moss, who stumbles across a drug deal gone wrong and absconds with a suitcase full of cash—drawing the attention of Anton Chigurh, a chilling, philosophically inclined hitman. It was famously adapted into a film by the Coen Brothers, which won four Academy Awards, including Best Picture.

10. The Road (2006)

A devastating portrait of love at the end of the world, The Road follows a father and son journeying through a gray, ash-covered post-apocalyptic America. They move through ruined cities and landscapes, foraging for food and avoiding roving bands of cannibals, clinging to each other. Stark and stripped of embellishment, the novel is arguably McCarthy’s most emotional work. It won the Pulitzer Prize for Fiction in 2007, was named one of the New York Times's 100 Best Books of the 21st Century, and was later adapted into a haunting film starring Viggo Mortensen.

11. The Passenger (2022)

After a 16-year hiatus, McCarthy returned with The Passenger, a dense, cerebral novel set in the 1980s which follows Bobby Western, a salvage diver unraveling a mystery surrounding a crashed jet and one of its missing passengers. Rich in philosophical dialogue and thick with atmosphere, it’s a sprawling late-career work that trades narrative clarity for metaphysical inquiry.

12. Stella Maris (2022)

A companion novel to The Passenger, Stella Maris unfolds entirely through dialogue between Alicia Western—a brilliant but mentally ill mathematician—and her psychiatrist at a Wisconsin mental hospital in 1972. The novel dives deep into mathematics, ontology, and the limits of human understanding, as Alicia questions the nature of consciousness and madness. Sparse and unflinching, Stella Maris functions as both a character study and a philosophical coda to McCarthy’s life’s work. Together, the two novels form a valediction steeped in grief, brilliance, and the search for meaning.