- New Arrivals

Fiction

- Historical FictionCrime & ThrillersMysteryScience-FictionFantasyPoetryRomanceChildren’s BooksYoung Adult

- Biographies & MemoirsHistoryCurrent AffairsTech & ScienceBusinessSelf-DevelopmentTravelThe ArtsFood & WineReligion & SpiritualitySportsHumor

Children’s Books

Lists

Blog

Gift Cards

My Lists

Games

The co-op bookstore for avid readers

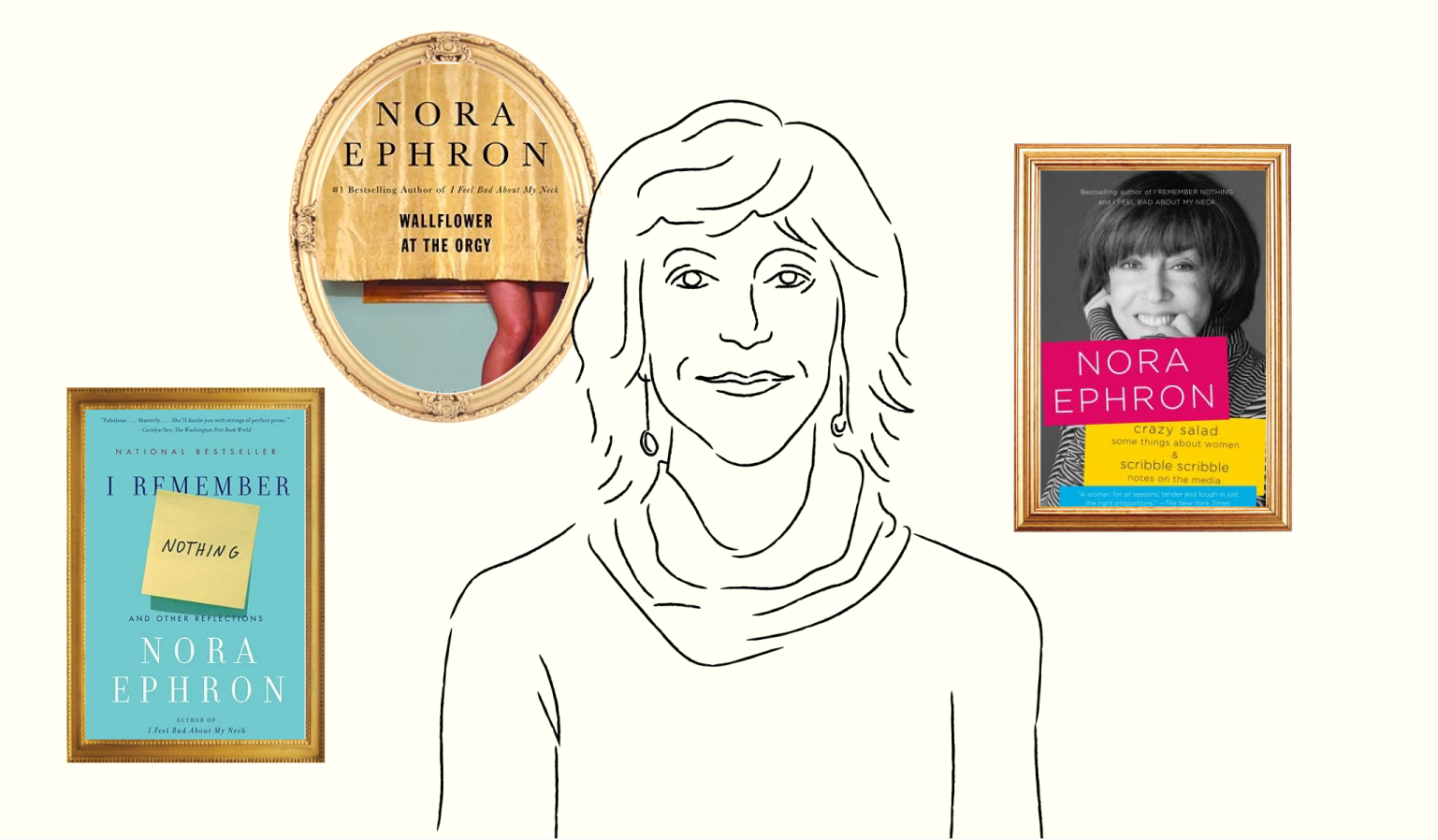

A List of My Favorite Nora Ephron Books for Her Birthday

Carrie Courogen is an author and editor based in New York. Her biography of Elaine May, Miss May Does Not Exist, is forthcoming this June from St. Martin's Press.

--

One of my favorite parts of the 2016 documentary Everything Is Copy is a sequence where a succession of Nora Ephron’s famous friends speak fondly about the verbal razor she carried in her back pocket. She was funny, they all say, and she was mean. It was part of her charm—when it wasn’t you that she was cutting to the quick. And, well, if it was? You just had to remember: She was funny, and often right.

On the page, as in life, Nora Ephron was very funny, and often very mean. I’m about to say something unpopular now: It’s the meanness that I like—or, rather, the ruthless commitment to quick-witted honesty. The more time passes and her legacy is pumped full of saccharine to be made comforting sweet tea to sip in cruel times, the more I wish people would acknowledge the zip of vinegar in her work. It’s in the films, if you’re paying close attention, but in print, it’s impossible to ignore. With a single sentence, she could slice anyone—even her bosses, her friends, or herself—wide open, often pulling off one of writing’s greatest magic tricks. Even when she was her most wicked, you were still on her side. Here are some of my favorites.

Wallflower at the Orgy

Ephron once claimed that “there’s nothing here extraordinary or brilliant” in her first collection of magazine pieces from the late-1960s, and I’ll give her that. But for completists, reading early Ephron in a state of becoming is a joy. Writing “I am in Helen Gurley Brown’s office because I am interviewing her, a euphemism for what in fact involves sitting on her couch and listening while she volunteers answers to a number of questions I would never ask” in a profile that manages to be both judgemental and compassionate, calling bullshit on a world she willingly concedes she’s part of? That’s the Nora Ephron I love.

Crazy Salad: Some Things About Women

If there’s one thing I’m never not thinking of, it’s Nora Ephron calling First Daughter Julie Nixon “a chocolate-covered spider” in her collection of columns about women written for Esquire. Ephron stressed that the work “is not intended to be any sort of definitive history of women in the early 1970s; it’s just some things I wanted to write about,” and, well, sure. But sharply writing about the things she found interesting—and bewildering, angering, and disgusting—about womanhood in the early ‘70s very much is a history, even if not definitive. To read pieces that range from personal to political now is to read a portrait of what it once meant to identify as a woman, and how much has changed—and how much hasn’t.

Scribble, Scribble: Notes on the Media

Scribble Scribble is a little inside baseball and a lot “you had to be there,” but its datedness makes it a terrific time machine to the early era of New Journalism. It’s peak Ephron, a deft blend of reporting and strong-willed, tough, and sometimes cruel observations. No one gets off freely: Not New York Post publisher and former boss Dorothy Schiff, not People Magazine (“It’s a potato chip. A snack. Empty calories. Which would be fine, really—I like potato chips. But they make you feel lousy afterward too.”), not even the outlets she was writing for.

Heartburn

Heartburn is so much more than the infamous salad dressing recipe that it spawned. (An aside: You do not need as much oil as it calls for, I promise.) As a thinly-veiled fictionalized memoir, the plot—a gossipy and self-effacing chronicle of the breakdown of her marriage to Carl Bernstein—is not what I’m drawn to. It’s her mastery of spinning the narrative, coming out not as the victim, but the hero of the story. If Ephron’s “everything is copy” motto taught me that there was nothing that could happen to you that couldn’t become a good story, Heartburn taught me to think about the power you hold when you tell it: “Why do you feel you have to turn everything into a story?” one character asks Ephron’s fictionalized stand-in. “Because if I tell the story, I control the version,” she replies.

I Feel Bad About My Neck: And Other Thoughts on Being a Woman

The first of Ephron’s pair of essay collections on the indignities of aging, I Feel Bad About My Neck is full of biting and shrewd pieces that feel like they’re being shared between conspiratorial glasses of champagne at lunch. But as much as I often turn to the collection for some sort of advice with her wry delivery, my favorite is “Considering the Alternative,” a somber and frank meditation on death. It’s a comforting reminder of Ephron’s range—she could be funny, yes, but also stunningly poignant—and the fact that she didn’t, of course, have all the answers. She was just as human as the rest of us.

I Remember Nothing: And Other Reflections

I feel bad for what I’m going to do here. What I’m going to do here is say that Nora Ephron was wrong about egg white omelettes. They are not, I am sorry to say, “tasteless,” nor are the people who eat them “misinformed.” But even though I vehemently disagree with her on this one, I love that she held such fierce opinions about such seemingly little things, and was so righteous in her belief that she went so far as to reprint a blog like “I Just Want to Say: The Egg-White Omelette” in I Remember Nothing. Like many of the pieces in the book, it capitalizes on the persona Ephron carried through her later life as a supreme authority who would tell you exactly what she thought you should do, and be hilarious while doing it. Whenever I feel like I am flailing, or am in search of unwavering advice, I return to I Remember Nothing, and remember that Nora was always right. Except when she was wrong.

Carrie Courogen is a writer and editor based in New York. Her biography of Elaine May, Miss May Does Not Exist, is forthcoming this June from St. Martin's Press.