- New Arrivals

Fiction

- Historical FictionCrime & ThrillersMysteryScience-FictionFantasyPoetryRomanceChildren’s BooksYoung Adult

- Biographies & MemoirsHistoryCurrent AffairsTech & ScienceBusinessSelf-DevelopmentTravelThe ArtsFood & WineReligion & SpiritualitySportsHumor

Children’s Books

Lists

Blog

Gift Cards

My Lists

Games

The co-op bookstore for avid readers

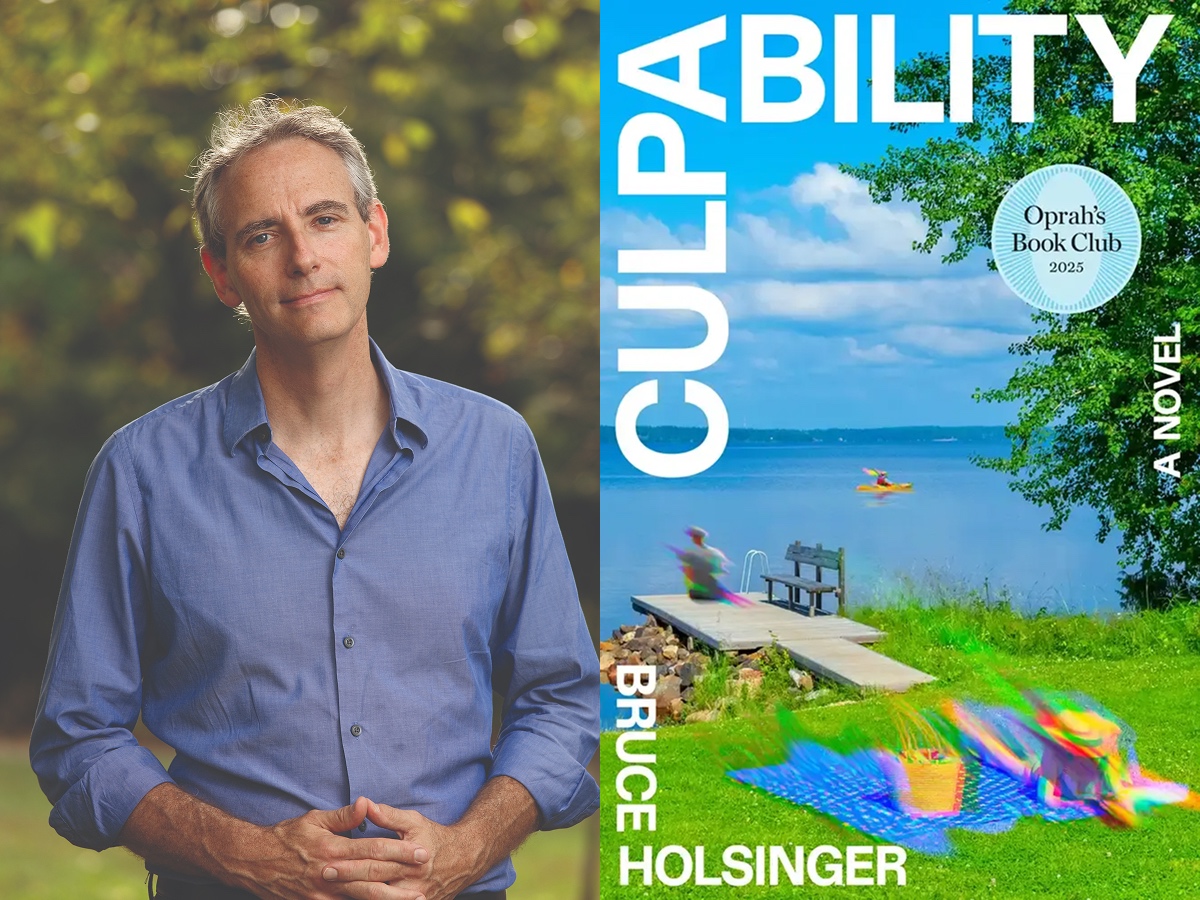

‘Culpability’ by Bruce Holsinger: An Excerpt

This summer, Oprah’s Book Club selection Culpability has readers racing through its pages—a tense, timely family drama that blends moral dilemmas, buried secrets, and the ethical challenges of artificial intelligence. Set against the Chesapeake Bay, the novel follows the Cassidy-Shaw family in the aftermath of a devastating crash that exposes fault lines in their relationships and forces them to confront the truths they’ve tried to hide.

Praise for Culpability

"I was riveted until the very last shocking sentence!" — Oprah Winfrey

"It's an incredibly nuanced book that brings up a lot of issues and, most importantly, allows you to talk about them in a way that's discernable. I'm recommending it to lots of people." — Kara Swisher, On with Kara Swisher

"The most of-the-moment novel I've read all year, and it's the book of the summer." — Real Simple

"If you want an engaging novel sure to spark great discussion about that thorny [AI] future, this is it." — Ron Charles, The Washington Post

"A propulsive, difficult-to-put down novel... The best kind of suspense usually comes from realistic situations where we are, as the title hints, somehow culpable for the bad things that happen to us, and that's true here." — Minnesota Star Tribune

Read on for an excerpt from the book.

CHAPTER 1

They call it the winner’s curse: a classic dilemma in corporate acquisitions when the parent company bids too high on the target firm, overvaluing assets, underestimating debt. You see it a lot in the wobbly real estate sector these days, and high tech is always vulnerable to this kind of predicament.

The case in front of me now—literally in front of me, in the form of a draft memo on my laptop, balanced between the dashboard and a raised knee as my family hurtles along this Maryland highway—concerns a straightforward merger of two solar energy companies. Our client got a bit exuberant during deal negotiations, accepting the smaller outfit’s hyped-up self-assessment of its market appeal. (Turns out most home solar customers don’t want “vintage” roof panels in Art Deco or Gothic Revival style.)

Now our client is getting cold feet. You can feel the change in the tone of the e-mails and in the mood of the Zooms, this mounting unease. The execs are looking for reasons to back out, and my job is to convince them otherwise, to show them why a withdrawal would be a big mistake.

I’ve got a solid argument. The legal bills entailed in a dissolution and inevitable lawsuit would quickly surpass the target’s inflated valuation minus its actual value. Our client, in other words, will lose far more money by pulling out of the deal than by staying in—and the difference will directly benefit my law firm. The memo on my laptop explains this uncomfortable irony with rhetorical delicacy and a touch of humor.

I am crafting a particularly artful sentence when we go over a bump in the road, causing the computer to jiggle on the bony knob of my knee. I catch the thing before it falls and rest it on my thighs, but there my words dissolve in a dazzle of sunlight, so I resume my original, more awkward position, crouched with a shin up against the glove compartment door.

Charlie laughs at something. I abandon my sentence and glance at him in the driver’s seat. The sight of my son’s handsome face in profile brushes away my irritation. His left elbow perches on the windowsill and his right arm rests at a languid angle on the central console, legs spread and knees a foot apart.

Charlie serves as our de facto driver today—not driving so much as monitoring our progress along this stretch of road. We have owned a SensTrek minivan for six months now, though when we put the vehi- cle into hands-free mode its maneuvers still unsettle me at times: abrupt decelerations, inexplicable lane changes, uncanny twitches of the wheel. But the car seems to know what it’s doing, and a certain freedom comes with relinquishing control, trusting our lives and limbs to the alien hidden somewhere behind the dashboard. Like an old player piano, its invisible mechanism worked by a ghost.

A glimmer of amusement lingers in Charlie’s eyes. “What?”

He shakes his head. “Just thinking.” “The game?”

“Yeah.”

“It’s Madlax Capital, right, the first match?” “That’s tomorrow. Today’s Tristate.”

“Didn’t you crush those guys at the winter classic?”

“Their goalie was injured and that dude’s a beast. He’s going to Michigan.”

“Ah.” I smile. Michigan, a school that tried and failed to recruit Charlie during junior year. “So maybe you’ll see him this upcoming season.”

“We play them in April. Away.”

“Love it.” In my head I start planning a spring trip to Ann Arbor.

Today’s destination is more mundane, a youth sports megacomplex on the Eastern Shore of Delaware. The tournament will be the final event of Charlie’s youth career, and we’re all five going over for a chaotic weekend with sixteen other families we have known for years, shuttling back and forth between the crowded hotel, the tournament fields, chain restaurants for large group dinners.

Already I miss these frenzied events. The prospect of spending Charlie’s last one together has induced a bit of preemptive nostalgia, tempered by excitement about what the following years might bring. Half the team will be going on to play college lacrosse. But Charlie is the undisputed star of his squad, a four-star recruit heavily courted by top programs. He committed to North Carolina a year ago, speaking with the coach out on the back deck while his mom and I waited in the house, distended with pride—tinged, now, with melancholy. Charlie departs in six short weeks for pre-season team camp and his freshman year, a prospect we are all mourning in advance.

With the possible exception of Alice, not her brother’s biggest fan. The two of them had another fight before we left, a tiff over a portable phone charger of disputed ownership.

In the visor mirror I catch a glimpse of our older daughter’s thick lenses, ice-blue with the glow of her screen. She brings a hand up to her nose and wipes a shining trail of snot along her cheek. I repress the urge to pass her a tissue, suggest she look out the window for a while. I know that any com- ment along those lines wouldn’t be welcome right now.

I angle the visor to check on Lorelei. Dust-pink headphones cup her ears as she scribbles in the notebook spread open on her lap. While I bang out a routine client memo, Lorelei is preparing for a working group in Montreal next week, on AI and quantum something-something. Her head bobs to the gentle contours of the road, her brows knit in concentration. This is how Lorelei works when she’s on a tear, whether in bed before the lights go off or in the air during a transatlantic flight: focused, noise-canceled, oblivious.

She glances up, perhaps sensing my gaze in the mirror’s narrow plane.

An automatic smile, smudges beneath her naked eyes.

Lorelei has been working too hard, especially over this last year, when the demands on her expertise seem to have reached a career high that bor- ders on destructive. She is too driven, too zealous, too eager to please all the claimants on her limited time. I can see what the over-commitment is doing to her.

Lorelei knows I worry, thinks I worry too much. I disagree. (She knows this, too.)

In the mirror she winks at me, a nothing meant to appease, before her gaze drops back to her lap.

I shift the visor again to look at Izzy. Our youngest sprawls on the bench seat in back, shoulder strap barely grazing her upper arm, fine-boned as a dove. Rather than turning around I shoot her a text—Tighten your seat- belt!—and watch for her reaction. She straightens and snugs the strap up her arm, giving my reflection a cheerful wave with her iPhone. Seconds later three thumbs-up emojis blip up on my screen, followed by a heart.

Unlike her sister, Izzy will be in heaven this weekend. It’s always worth taking her along on these things for the joy factor alone. A one-person cheering squad and a favorite sibling among Charlie’s teammates, she’ll spend half of every game performing handstands and cartwheels on the sidelines, chiding refs for bad calls.

I flip up the visor and scan the road ahead. Weekend beach traffic clogged the highway as we left Bethesda an hour ago and crossed the Bay Bridge, though by now the flow has lightened along this two-lane etched through soybeans and corn on the rural Eastern Shore. Cars whip along from the opposite direction while others pass our speed-limit-obedient minivan from behind. We’re in no hurry; face-off isn’t until 5:30. We’ve built in plenty of extra time to get to the complex for warm-ups, and I have another forty minutes to finish my memo.

With a sigh I prop the laptop on my knees and hunch down in my seat.

Again the screen displaces the road unscrolling ahead.

By the time we cross the state line (a quick glance out the passenger window: Welcome to Delaware with a wavelike swoosh in two shades of blue, “Home of Former President Joseph R. Biden, Jr.” emblazoned along the bottom), the memo is nearly done. In ten minutes I will e-mail a draft to the managing partner, completing this last work task before the family weekend officially begins.

I cock my head at the screen, staring down a final, problematic phrase, and—

“CHARLIE, STOP!”

Alice, screaming from behind me.

Charlie’s left hand clutches the wheel. Jerks. An alarm blares from the dashboard.

A screech of rubber. An impact.

A blinding explosion against my eyes and head. A sensation of weightlessness.

One flip. Two.

A horrible stillness when the minivan comes to rest, somehow back on its four wheels.

A chemical smell. Overpowering, close. A hissing from the engine.

Moans. Gasps. One sharp cry.

Through these seconds I am aware that an automobile accident is about to occur is occurring has occurred

Jagged fragments whirl in my head. And finally, stillness.

My ears ring, as if someone just pounded a gong inches from my skull. Charlie moves first. Below the ringing, in the depthless silence, there is the dull click of a seatbelt. My son pivots in his seat to look at me.

Blood trickles from his nose: the punch of the airbag. We are otherwise uninjured, the two of us.

For an endless moment we stare at each other. We stare and we stare because the one thing neither of us wants to do is to turn, to look, to dis- cover how the last ten seconds will echo down our lives.

Excerpted from Culpability by Bruce Holsinger. Copyright 2025 by Bruce Holsinger, Published by Spiegel & Grau.