- New Arrivals

Fiction

- Historical FictionCrime & ThrillersMysteryScience-FictionFantasyPoetryRomanceChildren’s BooksYoung Adult

- Biographies & MemoirsHistoryCurrent AffairsTech & ScienceBusinessSelf-DevelopmentTravelThe ArtsFood & WineReligion & SpiritualitySportsHumor

Children’s Books

Lists

Blog

Gift Cards

My Lists

Games

The co-op bookstore for avid readers

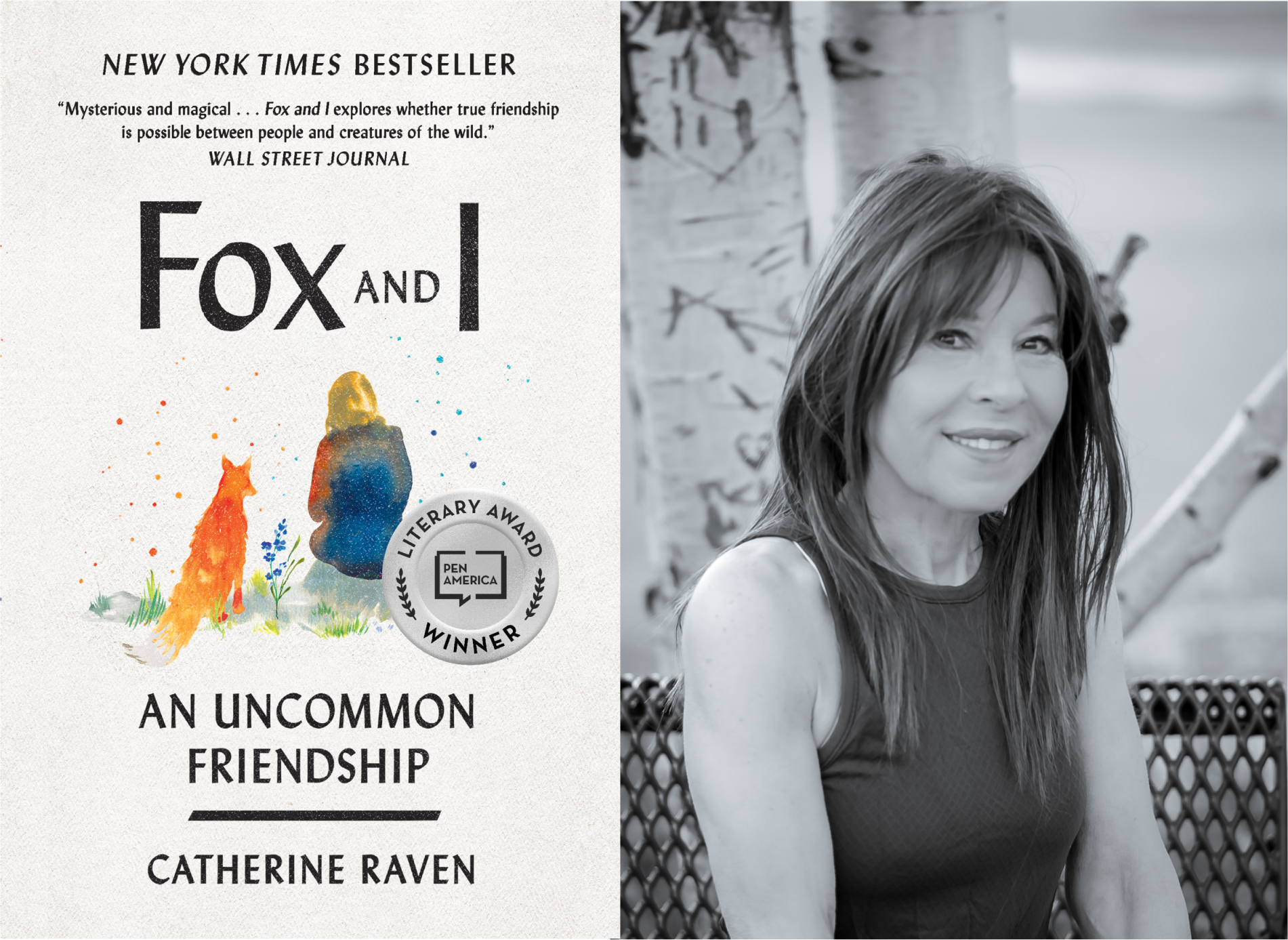

'Fox and I: An Uncommon Friendship' by Catherine Raven: An Excerpt

Nothing says summer like a visit to one of America's 63 stunning national parks. If you're looking for a book to read along the way or just want something to reignite your connection to the natural world, we recommend Catherine Raven's bestselling debut, Fox and I. The former park ranger's memoir about her remarkable and unlikely friendship with a wild fox was named a book of the year by Christian Science Monitor and won last year's PEN/E.O. Wilson Literary Science Writing Award.

While living in a cottage in the wilds of Montana, Raven notices that Fox begins visiting her property each day at the same time. She begins to read to him from The Little Prince and each day their friendship blossoms. This excerpt was reprinted with permission of the publisher, Spiegel & Grau.

While waiting for Fox’s 4:15 appearance, I thought about our upcoming milestone: fifteen consecutive days spent reading together—six months in fox time. Many foxes had visited before him; some had been born a minute’s walk from my back door. All of them remained furtive. Against all odds, and over several months, Fox and I had created a relationship by carefully navigating a series of sundry and hap-hazard events. We had achieved something worth celebrating. But how to celebrate?

I decided to ditch him.

I poured coffee grounds from a red can into a pot of boiling water, waited to decant cowboy coffee, and thought about how to lose the fox. Maybe he wouldn’t come by anymore. I opened the door of the fridge. “Have I mistaken a coincidence for a commitment?”

The refrigerator had no answer and very little food. But it gave me an idea. I drew up a list of grocery items and enough chores to keep me busy until long after 4:15 p.m. and headed out. The supermarket was in a small town thirty miles down valley, and I had to drive with my blue southern sky behind me. Ahead, black-bottomed clouds with white faces chased each other into the eastern mountains. Below, in the revolving shade, Angus cattle, lambing ewes, and rough horses conspired to render each passing mile indistinguishable from the one before. Usually, I tracked my location counting bends in the snaky river, my time watching the clouds shift, and my fortune spotting golden eagles. (Seven was my record; four earned a journal entry.) Not today.

Now that I was free to be anywhere I wanted at 4:15 p.m., I returned to my mercurial habits and drove too fast to tally eagles. Imagine a straight open road with no potholes and not another rig in sight. Shifting into fifth gear, I straddled the centerline to correct the bevel toward the borrow pit and accelerated into triple digits. Never mind the adjective, I was mercury: quicksilver, Hg, hydrargyrum, ore of cinnabar, resistant to herding, incapable of assuming a fixed form. The steering wheel vibrated in agreement.

The privilege of consorting with a fox cost more than I had already paid. The previous week, while I was in town collecting my groceries, I got a wild hair to stop at the gym. The only person lifting weights was Bill, a scientist whom I had worked with in the park service. I mentioned that a fox “might” be visiting me. “As long as you’re not anthropomorphizing,” he responded. Six words and a wink left me mortified, and I slunk away. Anthropomorphism describes the unacceptable act of humanizing animals, imagining that they have qualities only people should have, and admitting foxes into your social circle. Anyone could get away with humanizing animals they owned—horses, hawks, or even leashed skunks. But for someone like me, teaching natural history, anthropomorphizing wild animals was corny and very uncool.

You don’t need much imagination to see that society has bulldozed a gorge between humans and wild, unboxed animals, and it’s far too wide and deep for anyone who isn’t foolhardy to risk the crossing. As for making yourself unpopular, you might as well show up to a university lecture wearing Christopher Robin shorts and white bobby socks as be accused of anthropomorphism. Only Winnie-the-Pooh would associate with you.

Why suffer such humiliation? Better to stay on your own side of the gorge. As for me, I was bushed from climbing in, crossing over, and climbing out so many times. Sometimes, I wasn’t climbing in and out so much as falling. Was I imagining Fox’s personality? My notion of anthropomorphism kept changing as I spent time with him. At this point, at the beginning of our relationship, I was mostly overcome with curiosity.

I gripped a couple of firm white mushrooms in one hand and reached for one of those slippery plastic sacks with the other. The Timex face flashed on my exposed inner wrist. Forty-five minutes shy of 4:15p.m. The fox! Meeting a fox that I wanted to jettison suddenly felt more important than mushrooms for which I was driving sixty miles round trip. I shook the bag several times, but it refused to open, so I jammed the mushrooms back onto the shelf between some oranges and pushed my full cart to the registers. While calculating the time needed to drive home through a gauntlet of white-tailed deer along a two-lane road, I somehow ended up in the empty express-checkout lane. A cowboy rolled in behind me. The clerk observed my cart, raised her eyebrows, smiled, and said nothing. She was supposed to ask if I had found everything I was looking for; she wanted to ask if I could count to eight.

“Yes. Thank you,” I answered the unasked question, “but I regret abandoning some mushrooms at the last minute.”

Her eyebrows dropped. Eyes rolled.

I pulled a wallet out of my back pocket. “Shame about the mushrooms,” I said, flipping through the cash. Then I turned to the cowboy and noticed he was about 110 years old.

“Goodness. Just a little bunch of bananas.” I bent over his cart and peered inside. Nothing. Just bananas. “Didn’t even need a cart for that, did you?”

“Needed something to hold me up,” he said, “while waiting.”

For a moment I considered the remark, wondering if it had some underlying message. The cue hadn’t been in the cowboy’s words, but in his flinty-eyed stare. He’d expected an apology. Halfway home, I realized that he was annoyed that I was in the wrong checkout lane. I hated missing social cues. For every cue I caught too late, I worried about another few flying right over my head.

But more so, I worried about not being home when the fox came visiting. He was an uninvited guest and I couldn’t keep him waiting. Uninvited guests are quite unlike invited guests, whose entitlement (I imagine) allows them to overlook their host’s temporary tardiness. Invited guests will call, “Yoo-hoo!” and without waiting to see if “yoo” is even home, they will let themselves in. They will saunter over to the fridge and grab a drink. But uninvited guests are fragile, and you need to greet them punctually to minimize the discomfort inherent in their ambiguous status. Most problematic is the uninvited guest who knows he’s expected.

Unless I was home in forty minutes, a red fox would trot his reasonable expectation of hospitality down to my cottage, scratch the dirt, sniff the air, feign preoccupation, and expend his tiny reserves of patience and humility. Then he would slip away in a dreadful sulk. This could not be explained to a 110-year-old cowboy propped up by a five-banana cart, but it was true nonetheless.

Motoring down the driveway, I scanned the chubby hill across the draw. A vertical cliff with a sassy tilt to the north lay on top of the hill like an elegant pillbox hat. In the middle of the cliff, on a ledge tucked into a shaded pleat, a golden eagle rose from its nest. I ran upstairs, leaned onto the window ledge, and searched for the fox. When the tip of his tail breached the wheatgrasses, I led him with binoculars as though he were a grouse ahead of my 20-gauge. Leading, a traditional hunting skill, requires hunters to anticipate an animal’s speed and direction, keeping the barrel, sights, or scope just ahead of the moving target. Fox was an easy lead. His tail bobbed brazenly down the fall line. My college textbook claimed that wild animals instinctively elude their natural enemies. That may be true for a generic fox, but this specific fox was not eluding the golden eagle; he was bounding down the hill to the tune of the “William Tell Overture.”

Want to keep reading? Get 15% off Fox and I through June — plus another 10% when you take a free trial of Tertulia membership.