- New Arrivals

Fiction

- Historical FictionCrime & ThrillersMysteryScience-FictionFantasyPoetryRomanceChildren’s BooksYoung Adult

- Biographies & MemoirsHistoryCurrent AffairsTech & ScienceBusinessSelf-DevelopmentTravelThe ArtsFood & WineReligion & SpiritualitySportsHumor

Children’s Books

Lists

Blog

Gift Cards

My Lists

Games

The co-op bookstore for avid readers

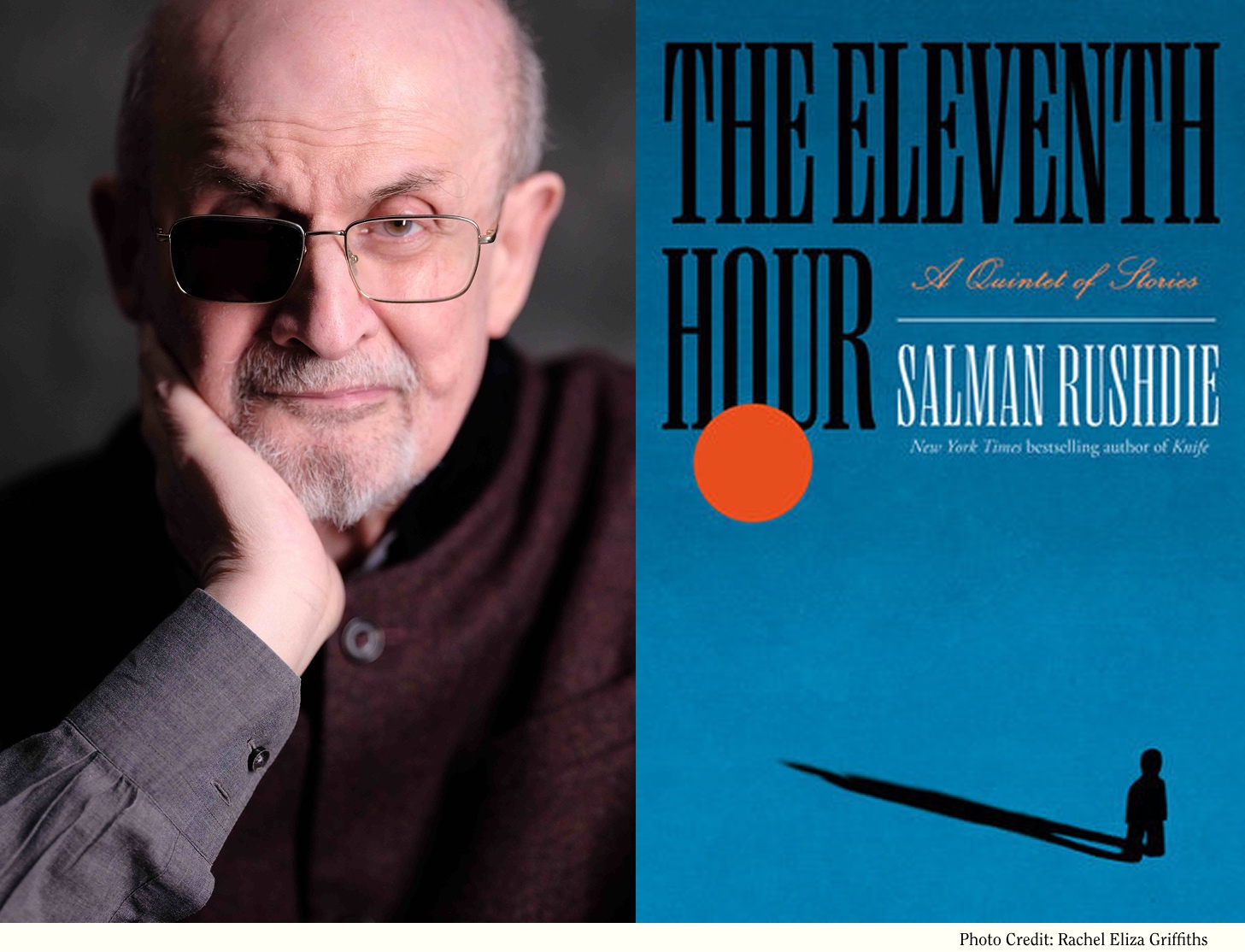

Read Your Way Through Salman Rushdie

Issued a fatwa. Stabbed on stage. Winner of the Booker Prize. Knighted by Queen Elizabeth II. Salman Rushdie's life is as captivating as the larger-than-life characters in his own novels—except the danger has been real, as is his legacy as one of the most vital voices in world literature. We may all know these salient details of his life but for readers who don't know his work, it can be intimidating to know where to start.

Since his debut in the mid-1970s, his novels, essays, and stories have moved across continents, histories, and mythologies, weaving together the intimate and the political with exuberant prose. His reputation rests not only on his role as a pioneer of postcolonial fiction—demonstrating how the English language could carry the cadences of Indian storytelling—but also on his unflinching confrontation of the cultural and political storms of his time, from the birth of modern India and Pakistan to the global tensions of migration, extremism, and free expression. The fatwa issued after The Satanic Verses made him an international symbol of artistic freedom, but it also overshadowed the range and vitality of his work, which extends far beyond that controversy.

To celebrate the release of his latest book, The Eleventh Hour, we’ve written a chronological guide to his work. Spanning epic historical novels, playful children’s tales, biting satires of contemporary America, and reflective essays, this guide shares a note about the resonance for each book to help readers determine which Salman Rushdie book to read. Staff picks are marked with an asterisk.

Grimus (1975)

Rushdie’s debut is a strange hybrid of science fiction, myth, and allegory that follows Flapping Eagle, a Native American who gains immortality and spends centuries wandering before arriving at Calf Island, which is ruled by the enigmatic Grimus. The narrative fuses Sufi mysticism with European speculative traditions, and though it failed critically and commercially, the book shows Rushdie’s earliest attempts to collapse boundaries between the real and the fantastical, a hallmark of his later work. The Los Angeles Times wrote, "Grimus is science fiction in the best sense of the word. It is literate, it is fun, it is meaningful, and perhaps most important, it pushes the boundaries of the form outward."

Midnight’s Children (1981)*

"In Salman Rushdie, India has produced a glittering novelist--one with startling imaginative and intellectual resources, a master of perpetual storytelling, " the New Yorker wrote upon the release of arguably the author’s most famous work. This novel traces the life of Saleem Sinai, born at midnight at the exact moment of India’s independence. His telepathic link to the other “midnight’s children” parallels the fractured destiny of the nation, and his own fragmented, digressive narration mirrors the messy history of postcolonial India. Rushdie draws from oral storytelling, Bollywood exuberance, and magical realism to create a dense, playful epic. The book reshaped English-language fiction from the subcontinent, asserting that the colonial language could carry the rhythms, jokes, and multiplicity of Indian experience.

Shame (1983)

Set in a fictionalized Pakistan, the novel traces the rivalry between two powerful men, and a woman whose suppressed desires eventually erupt in violence. Written during a period of political repression under Zia-ul-Haq’s regime, the book layers grotesque satire over real historical figures, exposing the violence and contradictions of Pakistan’s birth. Rushdie’s nameless narrator openly intrudes, blurring memoir and fiction, and his prose swings between biting caricature and tragic myth. It cemented his role as a political novelist willing to provoke through allegory. As the New York Times highlighted the book, “does for Pakistan what... Midnight's Children did for India” and there are many parallels in the structure and themes of the two books.

The Satanic Verses (1988)

The novel that sparked a global controversy and sent Rushdie into hiding Described as an “exhilarating, populous, loquacious, sometimes hilarious, extraordinary… roller-coaster ride over a vast landscape of the imagination” by the Guardian, the story begins with a plane explosion over the English Channel and follows the lives of two Indian expatriates, Gibreel Farishta and Saladin Chamcha. The pair survive the fall and undergo transformations—one into an angelic figure, the other into a devil. Interwoven are dream sequences retelling episodes reminiscent of Islamic history, including the controversial “satanic verses.” The global controversy and fatwa that followed overshadowed its literary qualities, but it remains a defining work of postcolonial fiction, capturing the volatility of cultural and religious borders.

Haroun and the Sea of Stories (1990)

Written for his son while Rushdie was in hiding, this children’s novel tells of Haroun, who journeys to the Sea of Stories to restore his storyteller father’s lost gift. Though whimsical, with talking fish and fantastical battles, it doubles as an allegory about censorship, imagination, and Rushdie’s own silencing after the fatwa. The style recalls Lewis Carroll and Arabian Nights, balancing wordplay with fable-like clarity, and it has become a staple of modern children’s literature.

Imaginary Homelands: Essays and Criticism 1981–1991 (1991)

This collection gathers essays on literature, politics, and Rushdie’s own position as a writer between cultures. He reflects on exile, language, and the responsibilities of the novelist, while also writing on contemporaries from García Márquez to V. S. Naipaul. The book contextualizes his fiction within broader debates about migration and postcolonial identity, and is valued for its articulation of the writer as both insider and outsider, carrying multiple homelands in imagination.

East, West (1994)

A set of short stories divided into three sections—“East,” “West,” and “East, West”—the collection ranges from Indian family dramas to Western pastiches and cross-cultural encounters. “The Prophet’s Hair” and “The Free Radio” dramatize South Asian moral dilemmas, while “At the Auction of the Ruby Slippers” and “Yorick” parody Western myths. The stories are compact compared to Rushdie’s sprawling novels, but they showcase his playful style and his ongoing exploration of hybridity.

The Moor’s Last Sigh (1995)*

Winner of the Whitbread Award for Best Novel (now the Costa Book Award) and Shortlisted for the Booker Prize

A multigenerational family saga set in Cochin and Bombay, the novel follows Moraes “Moor” Zogoiby, who narrates the turbulent history of his spice-trading family and the decline of cosmopolitan Bombay. Mixing myth, history, and political allegory, Rushdie critiques Hindu nationalism, corruption, and the erosion of pluralism in India. The prose is baroque and full of digressions, echoing earlier epics but sharpened by the urgency of 1990s Indian politics. Many critics regard it as his most direct portrait of Bombay and his most personal indictment of communalism.

The Ground Beneath Her Feet (1999)

Framed as a retelling of the Orpheus and Eurydice myth in the world of rock ’n’ roll, the novel follows Ormus Cama and Vina Apsara, whose love story plays out across decades of music, fame, and global culture. Narrated by photographer Rai, it blends pop culture references with mythological allusion, attempting to fuse high art and mass entertainment. Though polarizing in reception, it represents Rushdie’s engagement with globalization at the turn of the millennium.

Fury (2001)

Set in New York during the dot-com bubble, the novel centers on Malik Solanka, a former dollmaker and academic consumed by rage. His private turmoil unfolds against the backdrop of a city marked by celebrity culture and looming violence. The prose is restless, packed with cultural commentary, and the book captures an early-21st-century mood of dislocation. Though less celebrated than earlier works, it reflects Rushdie’s pivot to America and his interest in the anxieties of globalization.

Step Across This Line: Collected Nonfiction 1992–2002 (2002)

This collection of essays, journalism, and criticism spans Rushdie’s reflections on art, migration, politics, and his own experiences under the fatwa. Topics range from soccer to the war on terror, with a sharp focus on borders both literal and metaphorical. It reveals the breadth of his interests and his ability to move between cultural criticism and personal testimony.

Shalimar the Clown (2005)

A tragic love story set in Kashmir, the novel traces the fallout of a betrayed marriage that spirals into political violence. Noman (Shalimar) and Boonyi, Kashmiri villagers, embody both personal and national struggles, and the narrative shifts across continents as terrorism and revenge unfold. The book blends lush depictions of Kashmiri culture with an unflinching portrait of the region’s descent into conflict, making it one of Rushdie’s most politically charged works.

The Enchantress of Florence (2008)

A historical fantasia linking the Mughal court of Akbar the Great with Renaissance Florence, the novel introduces a mysterious woman who claims kinship with Akbar’s family. The story explores the fluidity of history and underscores the interconnectedness of East and West long before colonial encounters, while also reflecting Rushdie’s fascination with how empires construct their myths.

Luka and the Fire of Life (2010)

A sequel of sorts to Haroun and the Sea of Stories, this children’s tale follows Haroun’s younger brother Luka, who embarks on a quest to save his dying father by stealing the Fire of Life. Structured like a video game with levels and challenges, it reflects Rushdie’s awareness of younger readers’ media landscape, while continuing his defense of storytelling as a vital force.

Joseph Anton: A Memoir (2012)

Rushdie recounts his years living under the fatwa, narrating in the third person under the alias “Joseph Anton,” a name he adopted while in hiding. The memoir interweaves his personal struggles—failed marriages, isolation, clashes with publishers—with the larger political and cultural storm surrounding freedom of expression. Its tone is candid and combative, offering insight into the costs of living as a symbol rather than just a writer.

Two Years Eight Months and Twenty-Eight Nights (2015)

A fantastical tale drawing on Islamic and South Asian mythology, the novel imagines a world where jinn invade Earth, leading to a battle between reason and superstition. The time span equals “1,001 nights,” and the book reflects on Enlightenment values and contemporary extremism, cloaking serious concerns in fantastical extravagance.

The Golden House (2017)

Set in New York during the Obama years and leading up to the Trump era, the novel follows the wealthy, mysterious Golden family as narrated by René, a filmmaker neighbor. The Goldens’ secrets, reinventions, and eventual downfall become a mirror for America’s own anxieties about identity, wealth, and political corruption. The tone is satirical but elegiac, marking Rushdie’s sharpest engagement with contemporary American society.

Quichotte (2019)

A modern reimagining of Cervantes’ Don Quixote, the novel follows Ismail Smile, a traveling pharmaceutical salesman obsessed with television, who reinvents himself as “Quichotte” and sets off on a cross-country quest with his imagined son. His pursuit of a TV star is intercut with metafictional chapters about the novelist creating him. The book is both comic and tragic, satirizing media saturation, opioids, and disinformation, while celebrating the enduring power of literary archetypes.

Languages of Truth: Essays 2003–2020 (2021)

This later collection of essays spans literary criticism, reflections on storytelling, and commentary on politics and culture. Rushdie writes about ancient myths, contemporary literature, and the persistence of truth in an era of “alternative facts.” It serves as both a defense of imagination and a continuation of his role as public intellectual.

Victory City (2023) *

"Victory City is a triumph--not because it exists, but because it is utterly enchanting," wrote the Atlantic in a glowing review. Written as if it were a translation of a lost Sanskrit epic and set in 14th-century southern India, tells the story of Pampa Kampana, a girl blessed with divine powers who lives for centuries and narrates the rise and fall of the Vijayanagar Empire.

Knife: Meditations After an Attempted Murder (2024)

A National Book Award Finalist

A direct, intimate memoir reflecting on the 2022 knife attack that nearly killed him, this book considers the meaning of writing in the face of the stark reality of one's mortality. Less digressive than earlier works, it balances raw recollection with philosophical reflection, offering a rare stripped-down Rushdie voice. It stands both as personal testimony and as a continuation of his lifelong defense of imagination against violence.

The Financial Times wrote glowingly, “"Not just a candid and fearless book but--against all odds--a defiantly witty one... A 'reckoning', if not quite a catharsis, Rushdie's invigorating dispatch from (almost) the far side of death's door names and limits the attack as 'a large red ink blot.'"

The Eleventh Hour (2025)*

In his new book, Rushdie, who is now 78 and has faced more than a few brushes with death, grapples with life's final hour in a series of sparkling stories set across the three continents where he has created his art: India, the United States, and England. Kirkus Reviews praised the new collection, calling it "a provocative set of tales that, though with grim moments, celebrate life, language, and love in the face of death."