- New Arrivals

Fiction

- Historical FictionCrime & ThrillersMysteryScience-FictionFantasyPoetryRomanceChildren’s BooksYoung Adult

- Biographies & MemoirsHistoryCurrent AffairsTech & ScienceBusinessSelf-DevelopmentTravelThe ArtsFood & WineReligion & SpiritualitySportsHumor

Children’s Books

Lists

Blog

Gift Cards

My Lists

Games

The co-op bookstore for avid readers

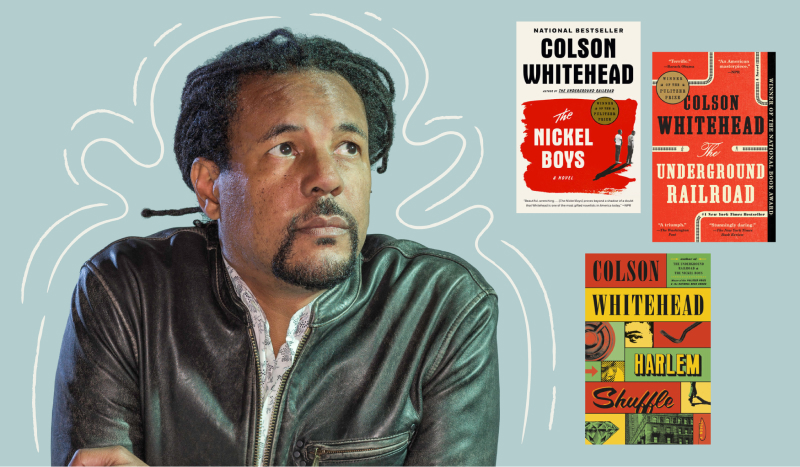

Reading Your Way Through Colson Whitehead

No single living American author defies categorization quite like Colson Whitehead. Whether writing about New York in a post-zombie apocalypse, following a Harlem crime caper, or taking a formidable trip through the Underground Railroad, Whitehead inhabits conventional narrative frameworks in literature and reinvents them from the inside out. One critic interpreted his technique of upending the literary formula as a way of revealing the flaws and shortcomings by which Americans have defined themselves.

Whitehead is the rare author to have won multiple Pulitzer Prizes for fiction, and his list of other achievements includes the National Book Award, MacArthur “Genius” grant, Whiting Award, Harvard Arts medal, Guggenheim fellowship and more. As one of our towering American contemporary authors, Whitehead is obviously required reading. But, it can be hard to know where to begin, given his range of subject matter and genres. Back in 2014, Dwight Garner’s New York Times review of a poker memoir by Whitehead foreshadowed the talent the author would flex across subject matters and genres in his career: “You could point him at anything — a carwash, a bake sale, the cleaning of snot from a toddler’s face — and I’d probably line up to read his account.”

In this Colson Whitehead reading list, which truly includes something for every reader, we bring you an overview of his work with our take on what makes each book special.

First, a bit about the author:

Born in Manhattan on November 6, 1969, Colson Whitehead was born Arch Colson Chipp Whitehead. (He’s used all those first and middle at some point in his life, but settled on Colson when he was 21.) One of four children, he grew up in New York with entrepreneurial parents who owned an executive recruiting firm. He attended Harvard University, where he became involved with the Dark Room Collective of young Black writers and became fast friends with poet Kevin Young, the current poetry editor of The New Yorker and director of the Smithsonian’s National Museum of African American History and Culture.

After graduating, he wrote for The Village Voice, one of the first (and most beloved) “alternative” weeklies. He’s written 11 books—primarily fiction, but some nonfiction—and his essays, short stories, and reviews have appeared in publications like The New York Times, The New Yorker, and Granta.

His Pulitzer-winning Underground Railroad was adapted into a hit TV show in 2021, winning a Peabody Award and Golden Globe for best miniseries. His other Pulizer-winning book, The Nickel Boys, is currently in pre-production, featuring Daveed Diggs and Hamish Linklater, with Whitehead as one of the head writers.

FICTION

Our Take: If you’re new to Whitehead, start with The Underground Railroad (2016), for which Whitehead won the 2016 National Book Award for Fiction and the 2017 Pulitzer Prize for Fiction. Follow it with The Nickel Boys, for which he won the Pulitzer Prize for Fiction again in 2020.

The Underground Railroad (2016)

Arguably the novel that catapulted Whitehead from a respected emerging author into a mainstream lit star, and the basis for the Amazon Prime Video series directed by Barry Jenkins, The Underground Railroad won Whitehead his first Pulitzer. The book follows the harrowing journey of Cora, a young slave on a Georgia plantation, as she escapes via the literal underground railroad, encountering different manifestations of racism and oppression in each state she passes through. Through vivid prose and surreal twists, Whitehead explores the brutal realities of American slavery and the resilience of those who fought against it.

The Nickel Boys (1999)

Whitehead’s second Pulitzer-winning book follows Elwood Curtis, a Black boy growing up in the 1960s Jim Crow South who is unfairly sentenced to a juvenile reformatory called the Nickel Academy—a school that is, in fact, a chamber of horrors. Based on Dozier Academy, a real reform school that operated for 111 years and was racially segregated until the 1960s—only closing in 2011—this powerful novel is called “a necessary read” by former President Barack Obama.

Next, we suggest reading Colson’s debut novel, which is ingeniously constructed with the pacing of a speculative thriller.

The Intuitionist (1999)

Whitehead’s first novel, which was nominated for the PEN/Hemingway award for fiction, explores warring factions of the Department of Elevator Inspectors: the Empiricists, who work by the book, and the Intuitionists, who check elevator safety by question and meditation. At the center is Lila Mae, the first Black female elevator inspector and an intuitionist, who just so happens to have the highest accuracy rate in the entire department. As she navigates through layers of corruption and intrigue, the novel delves into themes of race, technology, and societal power structures.

If you appreciate crime fiction at its craftiest…

The first two books in Whitehead’s crime trilogy are the only books of his that follow the same character, Roy Carney. Both books stand up very well on their own, but we suggest reading them in succession to truly get to know and understand Carney. “With these books, Whitehead has identified deficiencies in the noir genre, and injected beauty and grace into its often too-predictable and clichéd conventions,” raves Gabriel Bump’s review of Crook Manifesto in The Washington Post, “Whitehead has also again provided a direct challenge to how readers and the publishing industry should think of genre fiction compared with literary fiction.”

Harlem Shuffle (2021)

A finalist for the National Book Critics Circle Award in 2021, Harlem Shuffle is a novel about race, history, power, and Harlem, mixed with the genre of a period-set thriller. Ray Carney is a straight-laced salesman of furniture with a loving wife and second kid on the way. But he’s worked to be straight-laced, and when his cousin Fredie falls in with a crew who plans to rob a high-end hotel, he volunteers Ray to help out.

Crook Manifesto (2023)

Nominated for the top prize of mystery writing, the Edgar Award, Crook Manifesto continues a historical exploration of Harlem in the 1970s full of power and glory. In 1971, crime is rampant, and trash piles up on the streets as New York is careening toward bankruptcy. And, as if that weren’t enough, the Black Liberation Army is at odds with the NYPD. Ray Carney, back to straight-laced ways, just needs Jackson 5 tickets. And he just might be able to get them with help from his old police contact, Munson–but Munson needs a favor in exchange...

If you’ve already read a few of Whitehead’s books and are deadset on becoming a completist, you may already have your own sequence for working your way through them. Of course, there’s the chronological order of publication, which allows you to watch Whitehead’s style evolve. Then, there’s the option of reading his books in the order they’re set in—starting with The Underground Railroad and moving into post-apocalyptic Zone One. Whichever way you choose, his work invariably brings surprises and playful experimentation in genre and style.

John Henry Days (2001)

In his second novel, Whitehead intertwines the legend of John Henry, a steel-driving folk hero, with the modern-day story of a journalist named J. Sutter assigned to cover a festival celebrating Henry's legacy. The multi-layered and funny novel, which blends history, adventure, and wry anthropological wit and wisdom, caught the eye of author John Updike and set Whitehead up to receive the Macarthur “Genius” fellowship.

Apex Hides the Hurt (2006)

A comedic tour de force, Apex Hides the Hurt takes readers to Winthrop, a town that decides it needs a new name. The resident tech millionaire wants to call it Prospera; the mayor wants to name it in homage to the founding Black settlers; and the upper class don’t want it to change at all. So, they decide to hire a consultant. But a new name may be just the beginning. . .Through sharp wit and keen observation, Whitehead explores the complexities of language, branding, and the ways in which communities grapple with their pasts.

Sag Harbor (2009)

Whitehead grew up spending summers in Sag Harbor, New York, where this autobiographical, adolescent coming-of-age story is set. In fact, like the protagonist, Benji, Whitehead was once involved in a BB gun shooting contest. (Whitehead has the embedded BB near his left eye to prove it.) Benji spends summers in the real area of Azurest, a predominantly Black enclave where Whitehead’s family has spent summers since the 1940s. The episodic novel traces Benji’s summer with friends, almost-summer-loves, and a job slinging ice cream that will fill you with nostalgia and summer longing. Sag Harbor was reportedly in talks for development with HBO Max with Laurence Fishburne as executive producer.

Zone One (2011)

A mix of zombie horror and literary suspense, Zone One takes place in the lower half of Manhattan, the part of the island that’d been successfully reclaimed by armed forces after a pandemic has left only the uninfected and the infected—the living, and the living dead. The worst seems to be thankfully over, and Mark is clearing the lower part of the city of feral zombies. Unfolding over the course of three days, Zone One explores coming to terms with a fallen world.

NONFICTION

Our take: Whitehead’s two works of nonfiction are quite different in focus, one being the 2011 World Series of Poker and the other being a wide-ranging nonfiction exploration of New York. Both are surprising, original works that reveal as much about humanity as poker and New York history once you dig.

The Colossus of New York (2003)

Switching between third person to first person, Whitehead weaves individual voices, vignettes, and meditations into a nonfiction composition that paints a portrait of life in the city that never sleeps. Wide in breadth and exploring both the inner and outer landscapes of New York City, it’s a great read for on-the-go travel, a pre- or post-NYC trip, or when you just want a getaway within a book.

The Noble Hustle: Poker, Beef Jerky & Death (2014)

In 2011, Grantland magazine gave Colson Whitehead $10,000 to play at the World Series of Poker. While Whitehead had played poker before, he’d never played in a casino tournament–but he had six weeks to learn, so he boarded a bus to Atlantic City to learn the ways of Texas Hold’em.

The range of Whitehead’s oeuvre is remarkable, and it is inspiring to see him constantly challenging himself. He even makes it look easy with his wry sense of humor and unpretentious manner. (Just for fun, we’ll point you to Whitehead’s rules for writing from ages ago, that we stumbled upon in The New York Times archives.) Whichever way you choose to read your way through Colson Whitehead, you’re in for an unforgettable ride.