- New Arrivals

Fiction

- Historical FictionCrime & ThrillersMysteryScience-FictionFantasyPoetryRomanceChildren’s BooksYoung Adult

- Biographies & MemoirsHistoryCurrent AffairsTech & ScienceBusinessSelf-DevelopmentTravelThe ArtsFood & WineReligion & SpiritualitySportsHumor

Children’s Books

Lists

Blog

Gift Cards

My Lists

Games

The co-op bookstore for avid readers

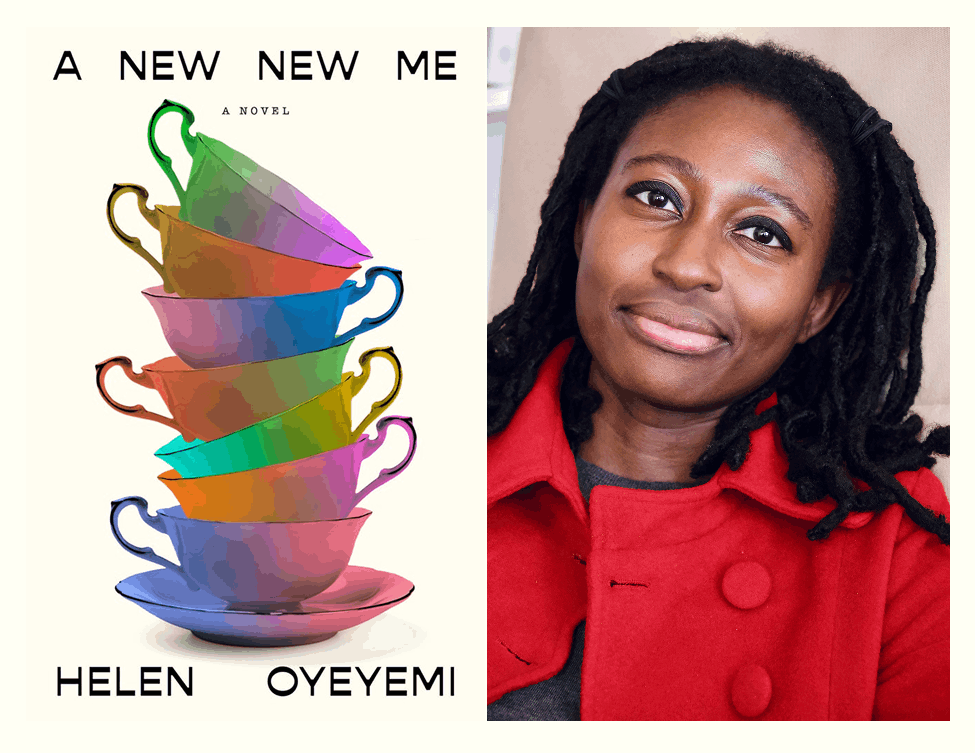

Reading Your Way Through Helen Oyeymi

“…for a zeptosecond…I was gripped by some sort of sensation reversed? As if the book had just shown me what it’s like to be read. Because of you I can cross over sometimes, think things I don’t think I think and believe things I don’t believe I believe.”—Kinga-A in A New New Me

I remember clearly the first time I read Helen Oyeyemi. I was on the beach in LA, where my twin sister lived at the time, paging through a copy of Zoetrope, the legendary short fiction magazine founded by Francis Ford Coppola and Adrienne Brodeur. That’s when I came upon an excerpt of Mr. Fox and was swiftly transfixed. “Oyeyemi, Oyeyemi,” I repeated silently to myself, trying to figure out who this was, where she was. I soon learned that the name is Nigerian, and that the author grew up in London. (She now lives in Prague.)

In the past twenty years, Helen Oyeyemi has published several works of fiction, including nine novels and a story collection. She wrote her first novel, The Icarus Girl, while still in high school. But the sheer number of works isn’t the point. Oyeyemi has elevated fiction to an entirely new echelon, one where story, time, and narrator finally get the freedom they deserve to play with one another, and with the reader too.

In an early interview, Oyeyemi described how, as a young writer, she would rework the endings of classic novels and fairytales. These departures appear throughout her work, reminding us that stories are fed to us. Consider Mr. Fox, where the narrative mutates as the title character kills off his heroines. Or The Icarus Girl, in which Jessamy Harrison reads a version of Little Women with a completely different ending from the Alcott novel–imagine Beth being sullen and insolent rather than the perfect martyr! Or in Parasol Against the Axe, a book passed from character to character changes depending on who reads it.

The nature of fiction is that anything can happen. But in Oyeyemi’s hands, that freedom isn’t taken for granted; it reshapes how we read and how we see ourselves as readers. We tend to be socialized into believing that stories are set in stone. In her world, they never are.

I don’t pretend to know everything about Helen Oyeyemi’s work. But I am a super fan, and her books have a way of surprising me—sometimes slipping sideways, sometimes running off in directions I never expect. Her latest novel, A New New Me (out August 26), is no exception. If you’re curious about her work or wondering where to begin, here’s a guide on what not to miss from a devoted reader.

A New New Me (2025)

What if, inside each one of us, there were multiple? A congress of selves convening each day, tossing ideas back and forth like a posse of peers growing old together? As an identical twin, I have an inkling of what it feels like to go through life with another “self” on the periphery. But in Helen Oyeyemi’s fantastic new novel, A New New Me, this brilliantly complex thought experiment is carried out all the way, and to perfection.

The narrator here is in fact seven points of view, or personalities, of the same person (with an eighth smartly hinted at in the wings, that ever-present “periphery”). Kinga Sikora has seven “selves,” Kinga-A through -G, each of whom report to each other in a shared diary from their separate days of the week. It’s a terrific accumulation not only of different viewpoints but also conflicting stories to make a satisfying whole. Through Kinga’s journey to find her “self,” her OG, we follow all of her Kingas as they struggle to trust one another and ultimately make a better, new regime for themselves.

Parasol Against the Axe (2024)

Hero Tojosoa brings a mysterious book with her to Prague that begins to behave strangely—it changes depending on who’s reading it. “Where are you?” asks the changeling book. “It seemed to Hero that the story she’d been reading was narrated by a person distinct from whoever it was that had written the words.” This is a perfect example of how, often in an Oyeyemi novel, the book itself becomes the narrator. In Parasol Against the Axe, we peer over Hero’s shoulder and vicariously become the character the book is speaking to.

I literally got chills the first time I read the question, “Where are you?” in this novel. I felt the book coming at me in the very best way. Then it prompted another thought: could that voice be Helen Oyeyemi, asking her reader and genuinely wanting to know what they are up to? If a writer like Oyeyemi wants to know, just out of curiosity, who her readers are, what they are thinking—what they are reading, even!—then I am all in.

What Is Not Yours Is Not Yours (2016)

In this collection of interconnected stories, the key, I think, is to play. There are both literal and allegorical “keys” throughout the book, but the enjoyment of reading goes beyond keeping track of what the symbols mean. My favorite short story of all time, by any writer, lives in this collection. “Presence” follows a married couple, Jill and Jacob, attempt to conjure each other’s presence from afar, and inadvertently summon the son they never had.

Oyeyemi is a master of turning time on its head. In “Presence,” decades pass in days, and Jill watches her son grow up, even though he never existed. The emotion this evokes– volcanoes, at least for me–brings a wash of love and regret that reminds me why I read. Don’t we all read to feel, to imagine, and to experience something greater than our fixed worlds?

Boy, Snow, Bird (2014)

As mentioned above, in a Helen Oyeyemi work of fiction, the entity that brings it all together is the so-called “narrator.” In Boy, Snow, Bird, Boy marries into a family that passes as white; her husband has a “white” daughter named Snow from his previous marriage. When Boy’s daughter Bird is born black, she casts Snow out, and we realize we are inside a version of the Snow White myth—except the “evil stepmother” is not who we expect. It’s a powerful story about surface identity and prejudice told by a narrator who “passes” as one thing but who is something else entirely, understanding for her own good reasons the power a surface can hold.

White Is for Witching (2009)

In White Is for Witching (a personal favorite, now vying to keep its place after reading A New New Me), Oyeyemi employs interchanging narrators, one of which is “26 barton road,” the house the main characters live in: “I am here, reading with you. I am reading this over your shoulder. I make your home home…I tell you where you are. Don’t turn to look at me. I am only tangible when you don’t look.” The house, like the book itself, detaches from the “object” it is and begins to speak. It becomes a voice, a narrator. It’s wonderfully unnerving and complicated. A voice that transcends character and even the author herself. The book speaks.

The Icarus Girl (2005)

I first read this novel soon after that fateful day on the beach holding my copy of Zoetrope. I read it again recently because I am working on my own novel about doppelgangers. Not that the mysterious TillyTilly is Jessamy’s doppelganger per se, but she is a twin in search of her lost sister, and Jess takes this sister’s place. “You have been so empty, Jessy, without your twin; you have had no one to walk your three worlds with you,” implores TillyTilly. In the Yoruba tradition, “twins are supposed to live in three worlds: this one, the spirit world, and the Bush, which is a sort of wilderness of the mind.”

A reminder, Helen Oyeyemi wrote this debut when she was only eighteen years old. The finely wrought, uncanny presence of the parallel world Jess encounters—sometimes described as horror, other times (mistakenly I think) as magical realism—is in my view simply, the best kind of fiction. It offers glimpses at what Oyeyemi went on to do in her later work, drawing readers into that wilderness of the mind, and daring them to keep going.

Also by Helen Oyeyemi: Peaces (2021); Gingerbread (2019); The Opposite House (2007).

Anne Hellman’s debut novel, The Indecipherables, will be published by Bantam in 2027. She has contributed stories and essays to Catapult, Tertulia.com, Hyphen, and other publications and is currently a Writing Mentor for Girls Write Now. She lives in Brooklyn, NY with her family.