- New Arrivals

Fiction

- Historical FictionCrime & ThrillersMysteryScience-FictionFantasyPoetryRomanceChildren’s BooksYoung Adult

- Biographies & MemoirsHistoryCurrent AffairsTech & ScienceBusinessSelf-DevelopmentTravelThe ArtsFood & WineReligion & SpiritualitySportsHumor

Children’s Books

Lists

Blog

Gift Cards

My Lists

Games

The co-op bookstore for avid readers

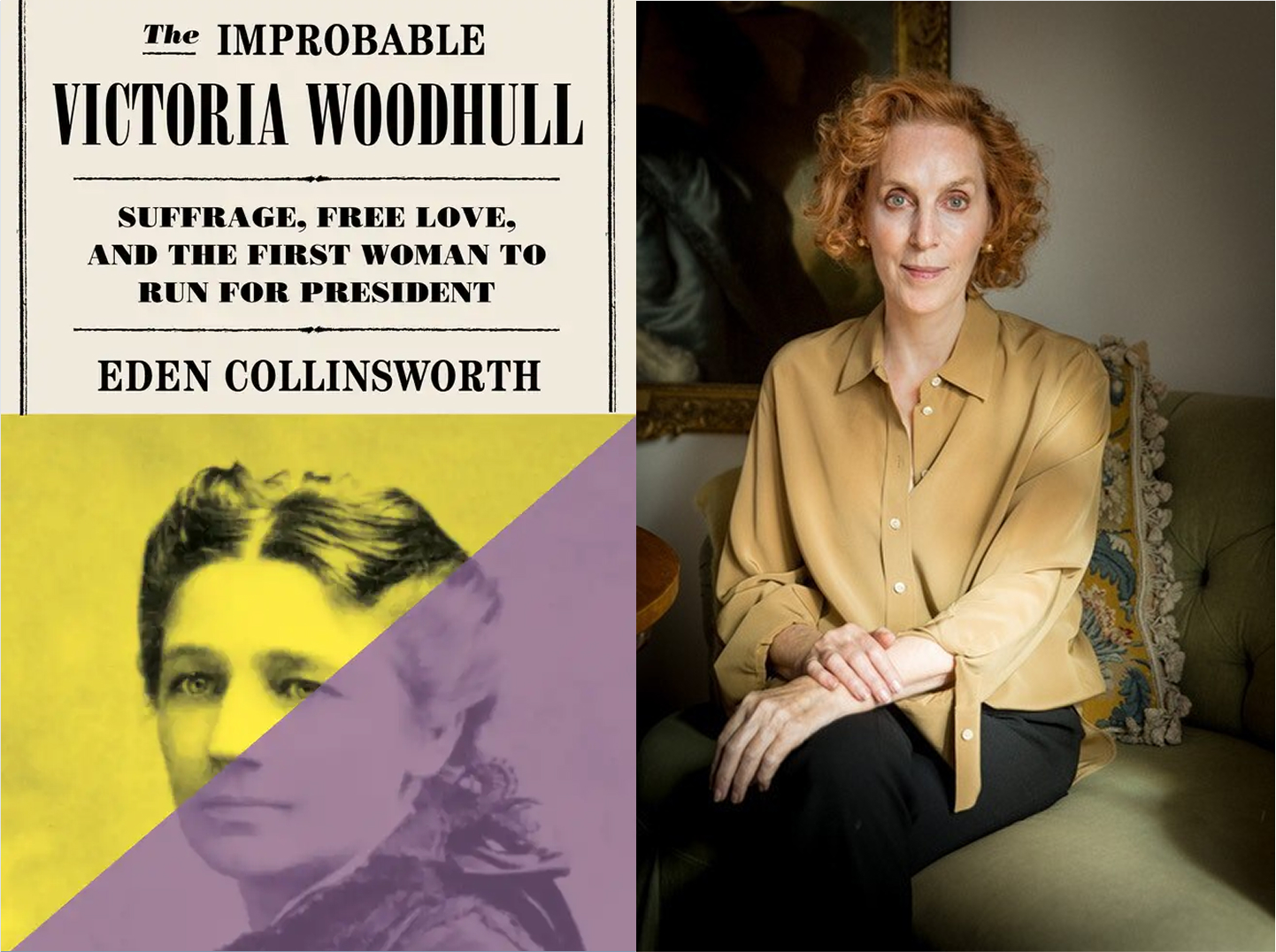

'The Improbable Victoria Woodhull' by Eden Collinsworth: An Excerpt

We often speak of people being ahead of their time—Victoria Woodhull truly was (she ran for President before women had the right to vote). Woodhull refused to allow social or class mores to dictate the bounds of her ambition. This allowed her to shatter every glass ceiling she encountered. Her surprising circumstances - and gumption (she was hardly the woman men – or women - expected her to be) - make Woodhull historical catnip for biographer Eden Collinsworth, whose extensive research on her life encompassed scouring family archives and over 170 other sources (books, periodicals, journals, and articles on, by, or about Woodhull).

Those sources, and Collinsworth’s brio as a practitioner of narrative nonfiction, inform the breadth of her barn-burning bio, The Improbable Victoria Woodhull: Suffrage, Free Love, and the First Woman to Run for President. “Collinsworth captures the twists and turns of her remarkable life with ingenuity and elan,” writes Sally Bedell Smith, delivering “a sympathetic, sweeping story with a fascinating cast of characters.”

The excerpt you are about to read involves a character and chapter in Woodhull’s life you probably don’t know about: the libel suit she brought against the mild-mannered director of the British Museum.

Early praise for The Improbable Victoria Woodhull

“A zesty biography of a colorful woman in the raucous Gilded Age.” —Kirkus Reviews

“A highly recommended, well-researched biography that brings Woodhull and her achievements to life.” —Library Journal *starred review*

“Victoria Woodhull provides a thrilling lens through which to interrogate the American dream. Full of twists and turns, Collinsworth’s audacious narration and nuanced understanding of the political machine of Woodhull’s time makes her work a gift for the reader. The Improbable Victoria Woodhull brings history to life with humanity, wit, and impeccable flair.” —Gay Talese, author of Bartleby and Me: Reflections of an Old Scrivener

The book releases on September 2 and is available for preorder on Tertulia. Read on for an excerpt from the book.

CHAPTER TWO

Mrs. Woodhull, a law unto herself.

Just as unexpected as the accusation of libel levied against Mr. Garnett was the identity of his accuser. The claimant was a fifty- four-year- old American by the name of Mrs. Victoria Claflin Woodhull, who, having lived a controversial life in the United States before moving to London, discovered that the British Museum was cataloging archival material she insisted contained unflattering references to her.

The events Mrs. Woodhull set in motion were preposterous enough that rumor of them surpassed Mr. Garnett’s belief until a subpoena was staring him in his flabbergasted face. Had he been wrongfully blamed for committing murder he could scarcely have been more stunned. Years of self- restraint prevented him from showing any visible signs of panic, but he was grateful for being seated behind a deskwhile reading the summons so that his knees could shake in secret.

Nothing remotely similar had ever happened to Mr. Garnett before and, with no other comparison, he struggled to find his bearings. So bewildering— no, so alien— was the claim that he was convinced his accuser must be deranged. The written material to which she objected appeared in a cataloged pamphlet that featured various news items from America recounting her past life, but he could find no immediate evidence that she’d taken legal action against those very newspapers at the time they ran the stories.

Mrs. Woodhull’s solicitor presented the details of her case: the proceedings would be stayed if (1) the museum were to remove the offending publications; (2) the museum’s trustees revealed the name of the vendor who supplied the publications to the museum; and (3) if the museum ran a public apology for having circulated libelous material.

“Mrs. Woodhull will incur any inconvenience to obtain justice,” was her solicitor’s fair warning.

The costs of defending a libel suit in Britain were markedly greater than in America and comparable European countries. Most people on the receiving end of the kind of letter sent by Mrs. Woodhull’s solicitor would have relented, not because they had a weak case, but because of the often- crippling expense of fighting the claim. The museum’s response was unequivocal: its duty was to provide a wide selection of literature to the public. Acquiescing to any one of the three demands would have profound consequences. As for Mr. Garnett, he deemed it to be an affront to the foundational principles of a public institution. He would not— could not— sanction that the material be withdrawn from the British Library simply because an evidently irrational female objected to it.

The fact that Mrs. Woodhull came from a bizarre, try- anything country with radical individualism at its heart encouraged him to believe that her nationality was the reason for this breach of civilized behavior and reasonable thought. He had not been to America, and the few impressions he had of its people were limited to what he read about them. Mr. Garnett had heard of the legendary Davy Crockett, whose distinctly American attitude was captured in a few short words: “If it’s right do it.” The French diplomat and political historian Alexis de Tocqueville’s book Democracy in America suggested that an American’s conduct was thought to be a proving ground for character. Charles Dickens embarked on a speaking tour in America and wrote of his admiration for its protean energies and the fact that an ambitious man in possession of a clever idea could become rich, but he came to the conclusion that its overstimulated inhabitants were ill- mannered. Anthony Trollope’s mother, Frances Milton Trollope, offered enlightenment on matters pertaining to America in her recently published book, Domestic Manners of the Americans, which recounted her travels there. It described the country’s raw immaturity and reported ten dencies of enthusiastic handshakes, first- name informality, and oversharing. As women often do, Mrs. Trollope assumed that when she judged something or someone to be unattractive, that something or someone should be unattractive to others; still, Mr. Garnett decided it probable that her observations were not ill- conceived. She provided two general warnings: first, that because the foundation stone of liberty in America hinged on the truism that every man is theoretically free to form his own opinions, Americans consider self- importance their birthright; and, second, that they did not share the Englishmen’s keen zest to be well- bred.

Despite the benefits that came from his reading about America and its people, Mr. Garnett was certain that there must have been an unknown something else, possibly a hidden depravity, that had stained Mrs. Woodhull’s reputation (even by American standards). He put aside his scorn for her and focused on the gravity of the situation after learning that, despite her last name, her litigious English husband was John Biddulph Martin, a partner in the fifth- generation private bank, Martins.The situation was grave indeed. It was the first time that a suit of libel had been brought against the museum and its esteemed trustees. As the museum’s keeper of the printed books, Mr. Garnett was charged with that same crime. Libel covers any published statement alleged to defame a named or identifiable individual in a way that causes loss in their profession or damages their standing in the community. The burden falls upon the accused party to prove that the material deemed libel is, in fact alone, true.

Not only was the American woman seeking damages for libel, she demanded an injunction against further issuance of the material in question.

“I shall not change my course because those who assume to be better than I desire it,” she had let it be known.

A trial by jury was scheduled at the Old Bailey— a stalwartly handsome and airless building where the Queen’s Bench Division deals with contract and tort (civil wrongs), judicial review, and libel. Mr. Garnett, along with the British Museum and its trustees, would be represented by Britain’s attorney general, Sir Charles Russell, QC, who was himself a trustee of the British Museum. Reputed to be the most adept cross- examiner in England, Sir Charles was renowned for his fierce intelligence, powerful recall, and verbal dexterity. Further, he demonstrated confidence in his understanding of the world, an unshakable sense of self- worth, a polite demeanor that belied a steeliness in confronting opponents, unflagging energy, a mastery of both nuance and detailed analysis, and, if needs must, an unsettling stare.

What no one was aware of— and what no one would have believed anyway— was that Victoria Woodhull possessed these same defining traits.

Copyright © 2025 by Eden Collinsworth. From the forthcoming book The Improbable Victoria Woodhull by Eden Collinsworth to be published by Doubleday Books, a division of Penguin Random House, LLC. Printed by permission.