- New Arrivals

Fiction

- Historical FictionCrime & ThrillersMysteryScience-FictionFantasyPoetryRomanceChildren’s BooksYoung Adult

- Biographies & MemoirsHistoryCurrent AffairsTech & ScienceBusinessSelf-DevelopmentTravelThe ArtsFood & WineReligion & SpiritualitySportsHumor

Children’s Books

Lists

Blog

Gift Cards

My Lists

Games

The co-op bookstore for avid readers

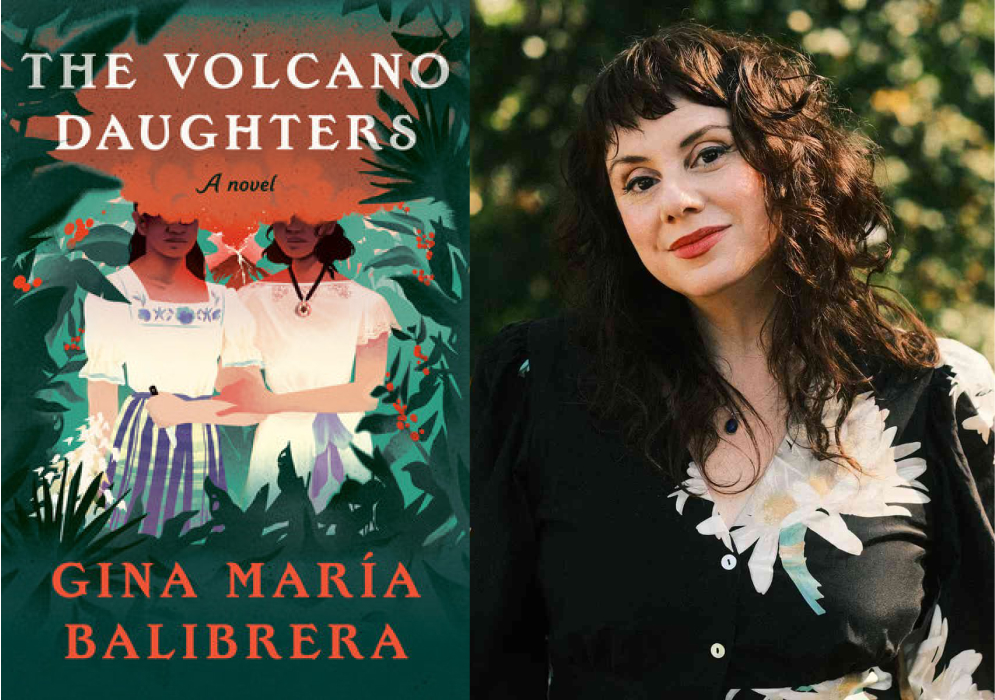

'The Volcano Daughters' by Gina María Balibrera: An Excerpt

Named a Most Anticipated Book by Vulture, Seattle Times, BookRiot and Electric Literature, Gina María Balibrera's searing and enchanting debut novel tells the story of two sisters, who are separated as children but are reunited after being forced to work in service to a tyrannical regime. After a genocide breaks out, the pair are once again separated as they flee the violence, until they are once brought back together under extraordinary circumstances.

“A new heir to the magical-realism throne.” —Seattle Times

“A bilingual, mythological, and original debut about resistance and survival.” —Vulture “A new book to be entered into the historical magical realism canon…A staggering tome of sisterhood, disaster, and myth. Readers can expect an imaginative roller coaster of emotion as the sisters do everything they can do to reconnect.” —Debutiful

The book releases on August 20 and is available for preorder on Tertulia at 20% off with code VOLCANO. Read on for an excerpt from the book.

Prologue

Here we are. All is still.

Cuando vos vas, yo ya vengo. We begin at la púchica root of the world.

Before we were made, the animals chattered. Jaguars spat the bones. Monkeys howled, volcanoes howled, the stars howled, cold and enormous. Someone listened and chose to destroy them, miren que, with a pair of large and ordinary hands. And after, those large hands that had made the beasts felt only emptiness. They itched to create something that could also create, beings that could carry life’s bright-blue thread through years and years, and so they rooted for just the right materials.

Poco a poco, new beings took shape. But the first, the mud creations were deemed soft and senseless; then the wood creations, bloodless and deformed. They were all cast away.

But maíz was tender, supple, fertile—talon of a wandering bird, a feather’s iridescence, a hard flake of jade, blood, milk, gold, gota a gota, formed a mano, a mano, a mano—then, slowly, we children de Cuzcatlán became too.

And us? There are four of us here in these pages. We are Lourdes, María, Cora, Lucía.

We cipotas were born of our mothers in a high, igneous sliver between the forest and the sea.

You see, before the massacre that killed us, we lived. We survived earthquakes and mudslides, the eruption of our volcano, Izalco. In the mountainside town where we all died (abandoned to rot, para más joder, piled like husks and leaves in a felled forest), our mothers had listened to radio piped in from the capital and smoked hand-rolled cigarettes in the coffee fields and never washed the black dirt from under their nails. We were in many ways like our mothers, even as we fought them, ignored them, hid from them, lied to them to run into the forest to kiss boys. (Except María—she kissed mostly girls.) What else could we do? The world was changing, everyone kept saying, but where was there for us volcano daughters to go?

Graciela was our friend. Like us, she was left for dead. But somehow she didn’t die in the massacre, as we did. Our cherita Graciela and her wannabe-chelita sister, Consuelo—when our souls discovered that they both had lived, pues, we hitched a ride on their life threads, followed along with them for the rest of their days.

Our own life threads, severed by our deaths, whip in the wind with our carcajadas. You’ve heard our carcajadas, our cackling laughter—it carries with it the stories of our mothers and grandmothers, the stories of ourselves. There are parrots in the field, and we’re always listening, siempre, a la vez. Sometimes we speak as one. Sometimes the wind scatters us apart, each a different seed. An eternal part of us remained after the massacre, the part that you hear, the voice telling you this story from all directions. We are gathering the threads of our lives, finding the words to write a new book of the people, to make our world. Miren que, the word makes the world.

Because you know what we’ve learned? Every myth, every story, has at least two versions. The growing of indigo and coffee, the movies and their magicians, the railroad tracing its long legs across our land like un pulpo, the story of a disgraced mother, a dictator, a nation’s beauties, a weeping woman beside water, a prophet. These mythic figures shift shapes, depending upon who tells their story and who listens.

Some morons say that we don’t exist, that we all disappeared in the massacre. But we live, seeded through the hills. Long ago we built temples to Ix Chel, goddess of the moon, of theearth, of war, of birth. She taught us how to weave, and we fell beneath her trance until the threads were taken from our hands. We are older than your sense of time. You pass us on the street. You squint into a mirror at home, painting your face to resemble ours. We stand on sunset rooftops shaking out your linens, and we take a long bus ride home. We teach your children in school; we take your temperature; we run for mayor of a bullshit town and they want to kill us for it. You sing our songs. You study our movements. We plan to outlive you. And we are here, telling you this cuentito.

Vamos a la vuelta. We all have work to do. Lourdes is putting everything in order, rewriting the Archives; María is charming whomever she pleases and slipping them a knife in case they need it; Corita is walking a field of bone-rich soil; Lucía is making sense of the dilution of skin. We are dead but we sing, we cackle, we lose our shit, we tell you exactly what we think, we don’t always agree, we do not tap-dance—more on that later. Trust us when we take your hands. We’ll bend time to tell you about nuestra hermana Graciela and that fucking warlock who held her captive. We’ll chase her sister, that silly güerita Consuelo, around the world. Consuelo, we adore her too, the idiot.

And oye, la Yina. Let’s not forget her. She’s the one putting our words on this page for you. We’re talking to you right now, Yina. Mind if we call you that? It’s what guanacos call Las Ginas, those cheap plastic flip-flops—but we wouldn’t expect you to know that, pocha. Yes, yes, you’re Salvi too, you’ve done your research, chele, you’re muy educada. You’re helping us tell our story. But fíjate: don’t get carried away with la poesía, ¿me entiendes? Don’t forget to listen. These words are ours, these stories ours.

And so now: All is silent and waiting. All is silent and calm. Listen to us. It begins.

Excerpted from The Volcano Daughters by Gina María Balibrera. Copyright © 2024 by Gina María Balibrera. Reprinted with permission of Penguin Random House. All rights reserved.